Review Psychological Instruments

View this article online at Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/jhbs.21601

OC 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

B O O K R E V I E W

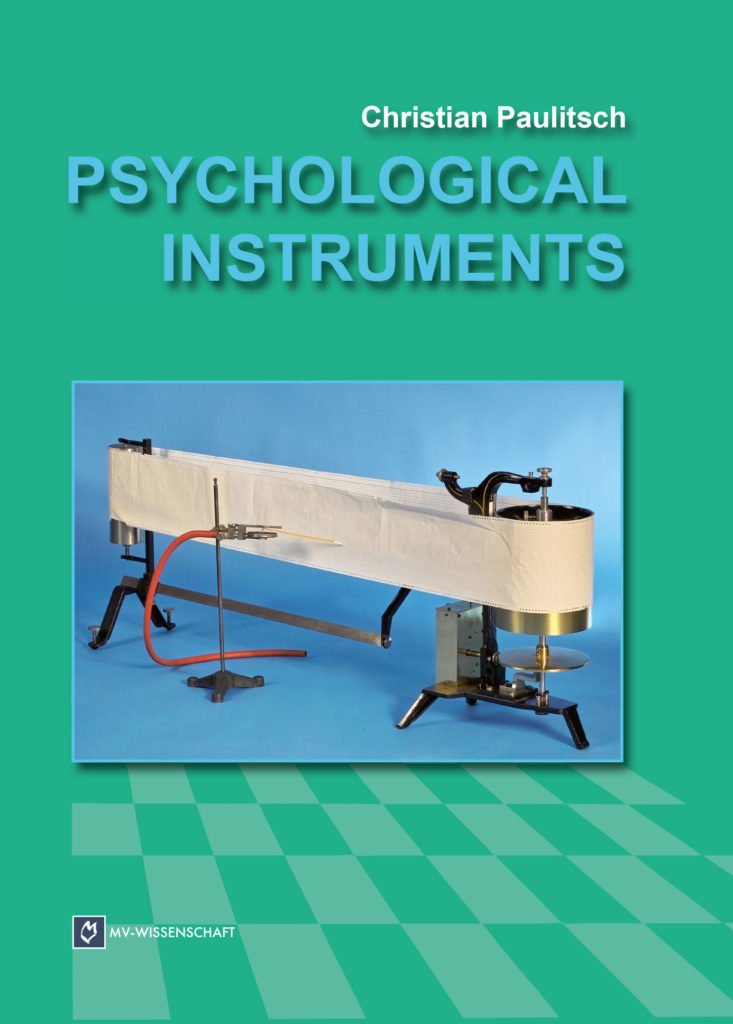

Christian Paulitsch. Psychological Instruments. Münster, Germany: Verlagshaus Monsenstein und Vannerdat OHG, 2011. 212 pp. 65.30 € (paperback). ISBN 978-3-86991-259-2.

Psychologists have a fondness for their old apparatus. There are extensive national and university collections at Harvard, University of Sydney, University of Oklahoma, Barnard College, University of Toronto, Centre for the History of Psychology at the University of Akron, Science Museum, National Museum of American History, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, the Adolf-Würth Center for the History of Psychology at the University of Würzburg and, of course, the small but holy Wundt collection at the University of Leipzig. Other small collections continue to surface—there is a small collection of historic instruments at Dalhousie University, there are also several key artifacts from the Montreal Neurological Institute at the Osler Library for the History of Medicine, McGill University. Stuart Blume (1992) once wrote that scientists show nostalgia for instruments, but not for outdated theories. This is particularly fitting for psychology, a discipline that rebranded itself as an experimental science in the late nineteenth century; instruments became a core part of its identity when it broke from philosophy. Horst Gundlach (University of Passau) has referred to the Hipp chronoscope as the totem of this movement (1996).

The current volume comes from the remarkable collection of instruments that was once part of the Institute for the History of Psychology at the University of Passau. In 1981, the Bavarian government established the Institute for the History of Modern Psychology at the University of Passau. The Institute built a historic collection of archival papers, books, trade literature, tests, periodicals, and instruments. There were over 5,300 artifacts in the instrument collection. In addition to the impressive collecting and preservation effort, the institute contributed much to the history of psychology through conferences, exhibitions, and teaching. In 2009 this collection moved to the new Adolf-Würth-Center for the History of Psychology at the University of Würzburg.

In Psychological Instruments, Christian Paulitsch provides an English version from his three earlier German books about the collection. Each German volume carries a selection of 50 items; the present one contains a total of 75 selections from those volumes. The entries for the latter volume have a full-sized color image on one page with a historical description on the other. The descriptions include the inventor, its purpose, how it works, and a convenient reference system to manufacturers, primary and secondary sources.

There are basically two parts to this book—instruments from experimental psychology and instruments from applied psychology. Both sections span from the iconic nineteenth century instruments to more recent twentieth century computerized equipment. The experimental sections contain instruments related to color mixing, touch, vision, acoustics, graphical devices, and reaction time. The instruments in applied psychology derive from railway industry, testing related to traffic, and many from commercial occupational tests.

I particularly liked the emphasis on applied instruments showing the scope and diversity of the original Passau collection. Applied instruments are often not taken as seriously as those connected to pure research and the big names in psychology. Consequently, one does not come across these as frequently in collections. However, these instruments reveal the extent to which psychology permeated everyday concerns in industry and transportation. They provide a fresh perspective on commercial and industrial heritage. For example, the Passau Institute preserved several instruments that tested attention and concentration from a time when machine operators learned to deal with an increasingly complex technological world. The Brake-Shoe apparatus (p. 117) tested “intense concentration.” A classic 1960s blue box tested for attention, concentration, and vigilance (p. 103). At the Zeiss Factory in the 1920s, Gustav Immig developed a wire-bending test that combined comprehension of shapes with manual dexterity (p. 159). Fritz Giese developed a handicraft test for girls that tested measurement by eye, threading cords, tying bows, and embroidery (p. 169).

Owing to his background as the restorer and conservation specialist for the Passau collection, the author, Christian Paulitsch, demonstrates a keen sense of the materials and technical functioning of the instruments. He has historically restored several of them. The stimulus-lever instrument based on Richard Pauli’s research on “focus of consciousness” contains a number of delicately interconnected levers that form a combined visual and tactile test (p. 81). Paulitsch informs us about the fascinating psychology behind this instrument; he also points to the skills and knowledge that went into making and using such an instrument. This is perhaps one of the deepest lessons from historic psychological apparatus, that creativity in the laboratory requires mastery (or at least appreciation) of an entirely different set of skills and knowledge. This was apparent in Wundt’s laboratory where many of the students had solid backgrounds in physics and electricity; it is equally apparent today where grad students in psychology laboratories must master software and electronics. Paulitsch’s ability to communicate clearly the complex functioning of the instruments helps us connect with this often-neglected source of innovation.

There is one important oversight throughout this volume—the author often did not add the basic historical data for an artifact such as date, maker, and provenance. This information is doubtless in the collection database, but leaving it out of each book entry leaves the reader with a historically generalized depiction of the instrument as archetype, without specific data about the artifact and its own history. F. Schulze may have invented the touch test instrument (p. 185), but information about who made the one in the collection, when it was obtained by its original users, who exactly used it, and when it was obtained by the museum can provide revealing (and often surprising) historical data about the life of an artifact. For example, the 1920s touch test apparatus carries evocative worn features from countless subjects and/or students. One can also make out the maker Zimmermann and an inventory number “Psychol. Inst. 72” not referenced in the text. While the general history of an object may take us in one historical direction, the features and provenance lead us into personal, pedagogical, manufacturing, esthetic, material, and geographical dimensions.

Aside from the shortcoming mentioned above, this book represents years of research and work in one of the more important collections of psychology instruments in the world. It contains a wide variety of instruments, with beautiful color images and comprehensive references. The author has provided an invaluable attention to the operation of the instruments.

REFERENCES

Blume, S. (1992). Whatever happened to the string and sealing wax? In R. Bud & S. Cozzens (Eds.), Invisible connections (pp. 87–101). Bellingham, WA: SPIE Press.

Gundlach, H. (1996). The Hipp chronoscope as totem pole and the formation of a new tribe: Applied psychology, psychotechnics and rationality. Teorie & Modelli, 1, 65–85.

BOOK REVIEW

Reviewed by DAVID PANTALONY, Curator of Physical Sciences and Medicine, Canada Science and Technology Museum, ON, Canada; Adjunct Professor, History Department, University of Ottawa, ON, Canada.